Wheat and the Water Cycle

Water comes to us in many forms. We receive it through our water taps from pipes that connect to rivers, reservoirs, and aquifers. We also receive various forms of precipitation, including rain from the clouds. We even receive it frozen, in the form of snow in the winter!

In Washington state, different parts of the state get different amounts of precipitation. The areas west of the Cascade mountains tend to get up to 50 or 60 inches of rainfall, and the areas east of the mountains usually get less than 18 inches of rainfall each year!

On the farms of eastern Washington, precipitation in the forms of rain and snow are very important to help grow wheat. In the winter months snow builds up on the fields.

As the winter warms up and turns into spring, our snow melts. All those snowflakes melt and they turn into water droplets. Those water droplets drop down into whatever surface they were resting on during the winter. In this case, the water drops into the farmer's soil. This is known as moisture in the soil. In the spring, we often get more precipitation that adds to the other moisture.

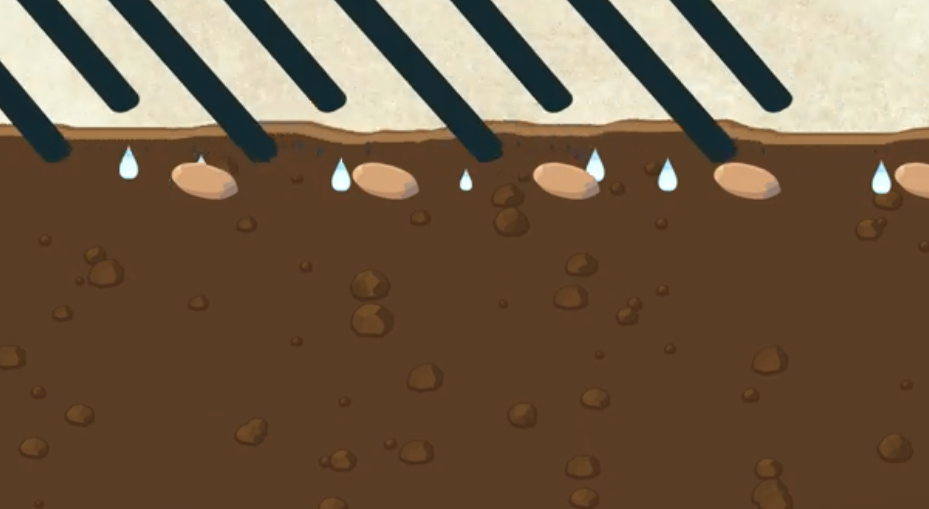

On warm days, some of the moisture in the soil evaporates back up into the air. When the soil is ready in the spring, wheat farmers plant their spring wheat crop into the soil. They put the seed at just the right depth in the moisture, so that the seeds can have a nice, moist place to grow.

As the seeds sit in the soil, more moisture tends to evaporate into the air. This moisture collects and makes droplets again, and they end up forming clouds. The rest of the water drops that remain in the soil begin dropping slowly down within the soil.

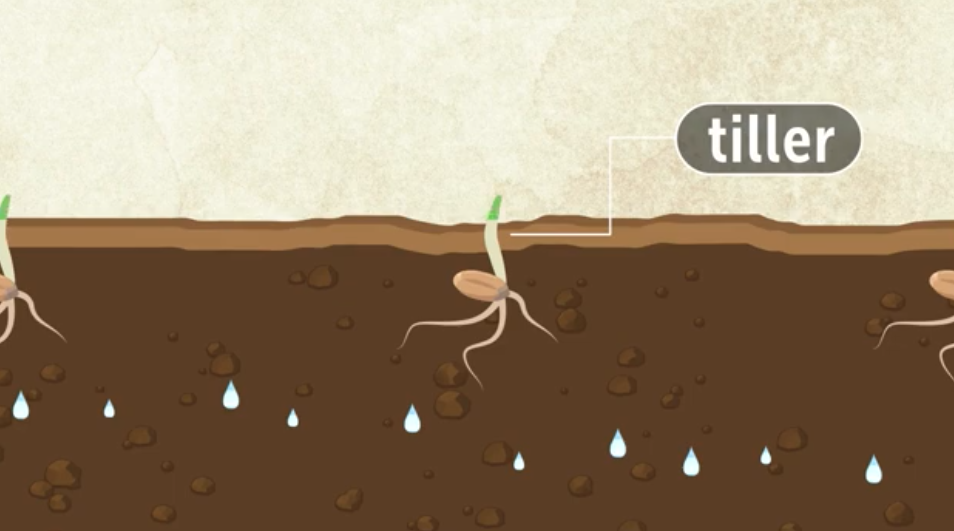

While the wheat seeds sit in the moist soil they are busy growing! After a few days, the wheat seed germinates, which means that the seed has started to grow and has broken the seed coat. Meanwhile, our water drops, or moisture level, naturally drop further down into the soil.

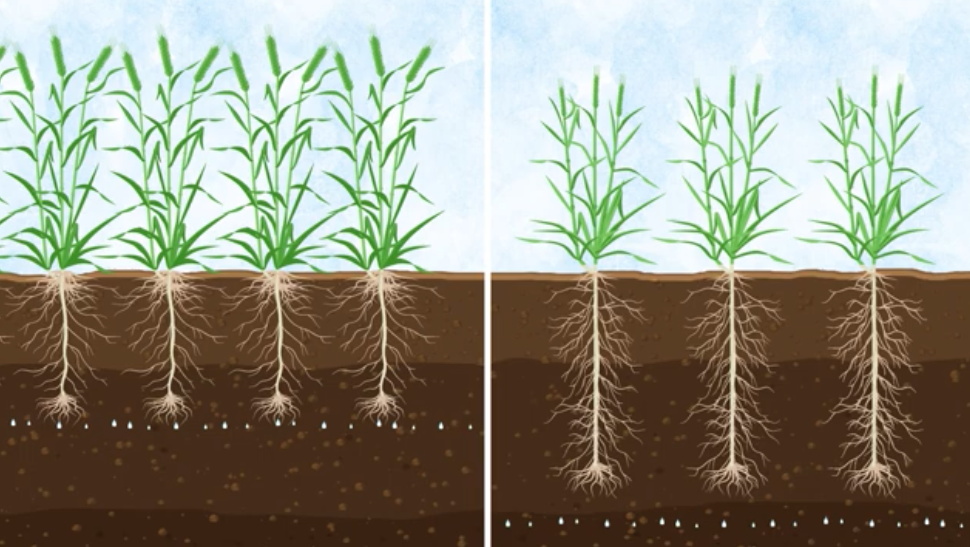

Roots form and the first shoot, also called a tiller, grows up from the ground. The roots’ job is to feed the plant. They start to follow the moisture level further down into the soil.

As the wheat plants continue to grow, they start the jointing and booting process. During jointing the shoots continue to grow forming nodes and eventually leaves.

During booting the head of the wheat plant grows from the top of the stem and has the last leaf wrapped around it.

Meanwhile underground the roots continue to chase the moisture level downward.

The plants grow, and their root systems continue to feed the plant water and nutrients found in the soil.

The plants grow, and their root systems continue to chase the moisture level downward as they feed the plant water and nutrients found in the soil.

Now the plant has grown large enough to start producing a head. That’s where the kernels are kept. Again, the roots grow deeper, chasing the moisture level down.

Sometimes we get spring rains that help keep the soil moist near the top of the surface so the roots don’t have to grow so deep to find water. BUT, sometimes we don’t get enough rain in the spring and farmers face what’s called a “drought”. By the middle of summer, the wheat plants really display how much rain we received in the spring.

During this stage of growth the wheat plant is full-grown and starts to ripen from green to a golden yellow.

During an average year, the wheat plants grow big, plump heads and the plants stay green for awhile.

During a drought, when the plants have gotten very little water to drink, the plants have tiny heads and the leaves are thin. During a drought, the wheat plants ripen faster, and turn yellow quickly.

Here are photos of a Washington wheat field during an average year, and one during a drought.

Once the wheat plant is ripe, it is ready to be harvested. Farmers use a big machine called a combine to cut and separate the kernels from the stalk and leaves.

Meanwhile, the leftover water that we received from snow continues its journey down into the ground.

It travels hundreds of feet over a long period of time, eventually arriving at our underground river system, called the aquifer.

There, our old snowdrop joins the aquifer.

While in the aquifer, our snowdrop could become drinking water for our homes through the pipes that pump water up from the aquifer to the surface.

Or it could continue along the aquifer and eventually make its way to the ocean.

Once at the ocean it could stay there for a long time, OR it could evaporate up into the air and form a cloud.

And eventually end up as another snowflake or rain drop, ready to help our wheat farmers again!